Zaha Hadid lived and worked in London for most of her life, and her architectural studies were saturated by rigorous explorations of the city’s latent potential. That her practice only completed a handful of projects in the city should not prevent us from asking an important historical question: What role did London play in shaping her thinking? Were there key themes that she exported from her early explorations to her built projects around the world?

Zaha Hadid: Reimagining London, the first exhibition held by the Zaha Hadid Foundation (ZHF), explored these questions. The foundation was established in 2013 by Zaha Hadid to broaden access to and understanding of architecture, however progress was slowed by her sudden death in 2016. Split across two sites in London, one in Clerkenwell and the other near Tower Bridge, the foundation preserves Hadid’s legacy and life’s work while also supporting students from diverse backgrounds through scholarships and grants. A team of 12 students from The Courtauld Institute of Art curated this exhibition, which ran for almost a month in June. The ZHF is one of the organizations partnered with the institute to support the teaching program by giving students a practical understanding of the museums and galleries sector.

Reimagining London was installed in a single windowless room in Hadid’s former Clerkenwell offices. Beginning with her graduate project Malevich’s Tektonik, viewers were taken on a chronological journey through a series of projects sited in London. From the outset, Hadid was clearly interested in pushing against what she referred to as “the conservative element” in a 2015 City Lab interview. In her drawings, forms were inverted, the ground plane was shattered, and simple briefs were stretched to include (seemingly) conflicting elements.

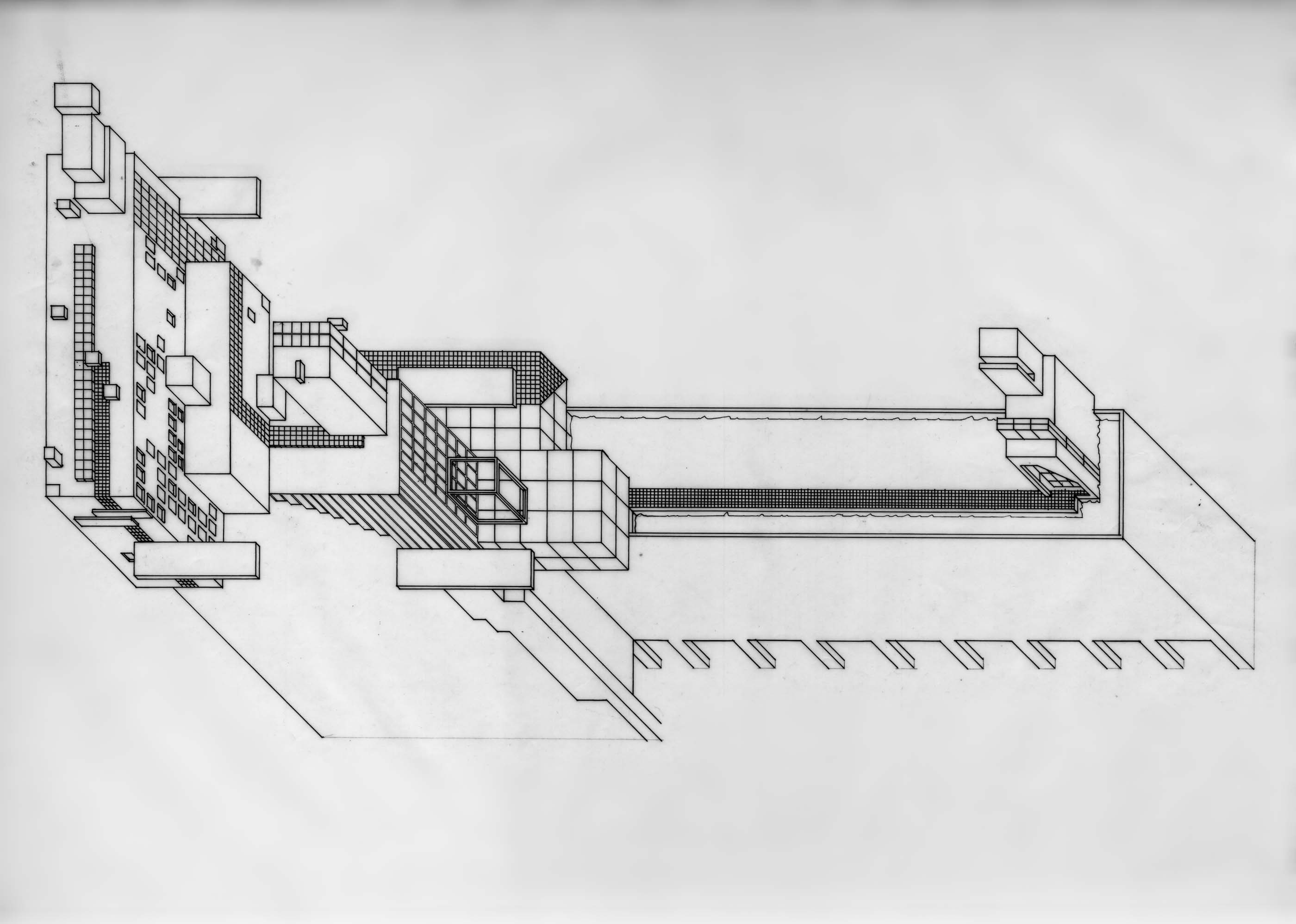

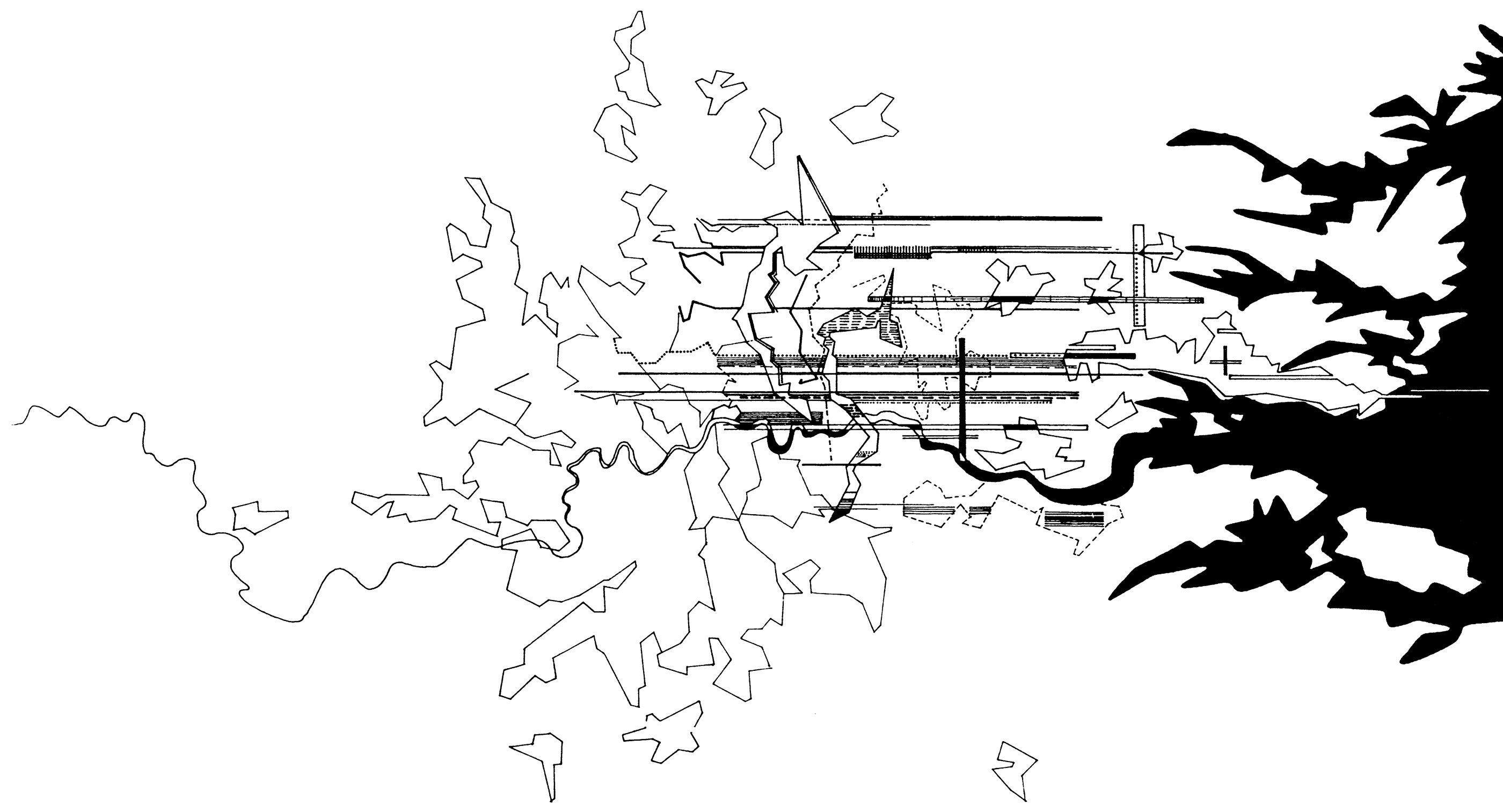

In addition to questioning conventions of architectural representation, Hadid’s early work additionally challenged the city itself. In her work, the existing urban context was a malleable object ripe for intervention, as seen in the roof plan drawing for Museum of the Nineteenth Century, where Hadid’s insertions land cantankerously above Southbank Centre.

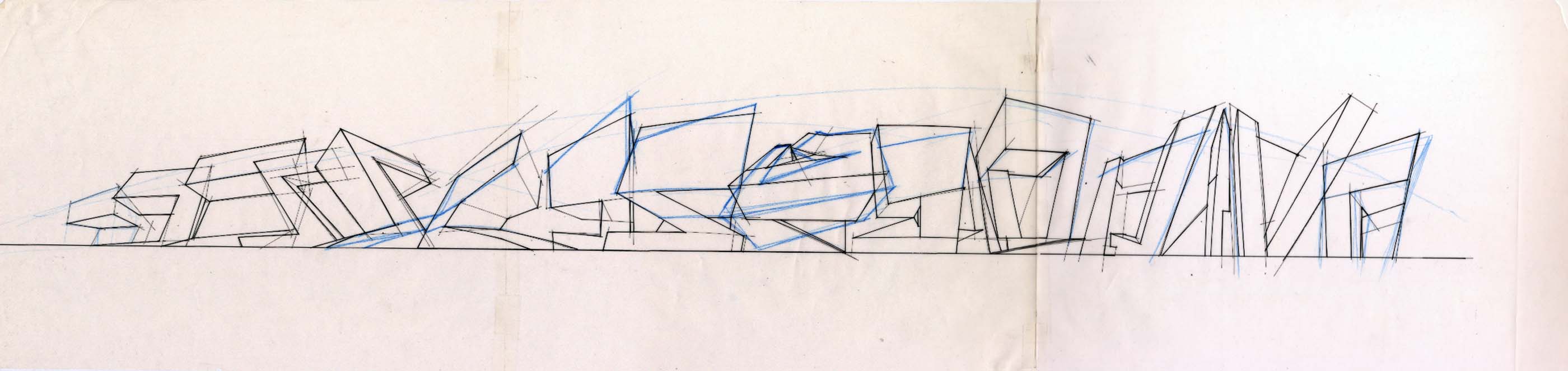

In Grand Buildings, Trafalgar Square project, interior spaces are secondary to an emphasis on action, activity, and the shock factor of bold formal moves. A painting and accompanying sketches from Hadid’s London 2066 project (1991) signaled her ability to translate components of the city into oblique, cascading fields of forms. In many ways this work built on ideas seen in the earlier 1983 competition drawings for The Peak, a leisure club secreted away in a Hong Kong hillside. The images for both projects simulate a zero-gravity space where elongated prisms are propelled towards and away from the horizon. Hadid’s vision for London was informed by the 20th-century precedents of

Hadid Foundation

Constructivist aesthetics and modernist megastructures and imagined topography, urban form, and movement condensed into a singular landscape. Evoking a similar tension between solid and void, Hadid’s Pancras Lane models again experimented with urban space as a highly pliable substrate: In a few of the models, the building’s circulation is seen as a subtle overlay onto the existing ground while in others a glass box encapsulates the built mass, making the space around the form equal in value to the form itself.

At the center of the gallery, the curators displayed two of Hadid’s student sketchbooks from her time at the Architectural Association. The pages contain a frenetic mix of quickly sketched ideas in a thick, green marker and tutorial and lecture notes, as well as larger, more rigorously thought-through plan drawings. As the curators noted, seeing her handwritten thoughts, feelings, and reflections during her formative experiences as a student feels intimate. The immediacy and lack of perfection displayed in these sketchbooks is surely an inspiration to current architecture students, as it demonstrates how great ideas can flourish when the student simply uses whatever is at hand—even if it’s a green marker—to get ideas on paper. That a broader set of pages was not presented feels like an oversight, as the viewer’s curiosity is unlikely to be quenched by just four pages.

Valley, 1991 © Zaha Hadid Foundation

It’s worthwhile to compare this show of Hadid’s formative work to a concurrent show staged on the other side of London. In Fulham, Roca Gallery, designed by Zaha Hadid Architects, is hosting Everything Flows: Zaha Hadid Design, an exhibition that presents items produced much later in her career through Zaha Hadid Design, which was founded in 2006. (The show runs until December 22.) The objects on display range from lighting to footwear and jewelry and again establish that Hadid had an all-consuming formal vision. Much like the early Pancras Lane models invited viewers to imagine the feeling of fluid inhabitation, so too the later Liquid Glacial Tables, from 2012, invite onlookers to engage with an acrylic piece which looks like poured water frozen in time.

© Zaha Hadid Foundation

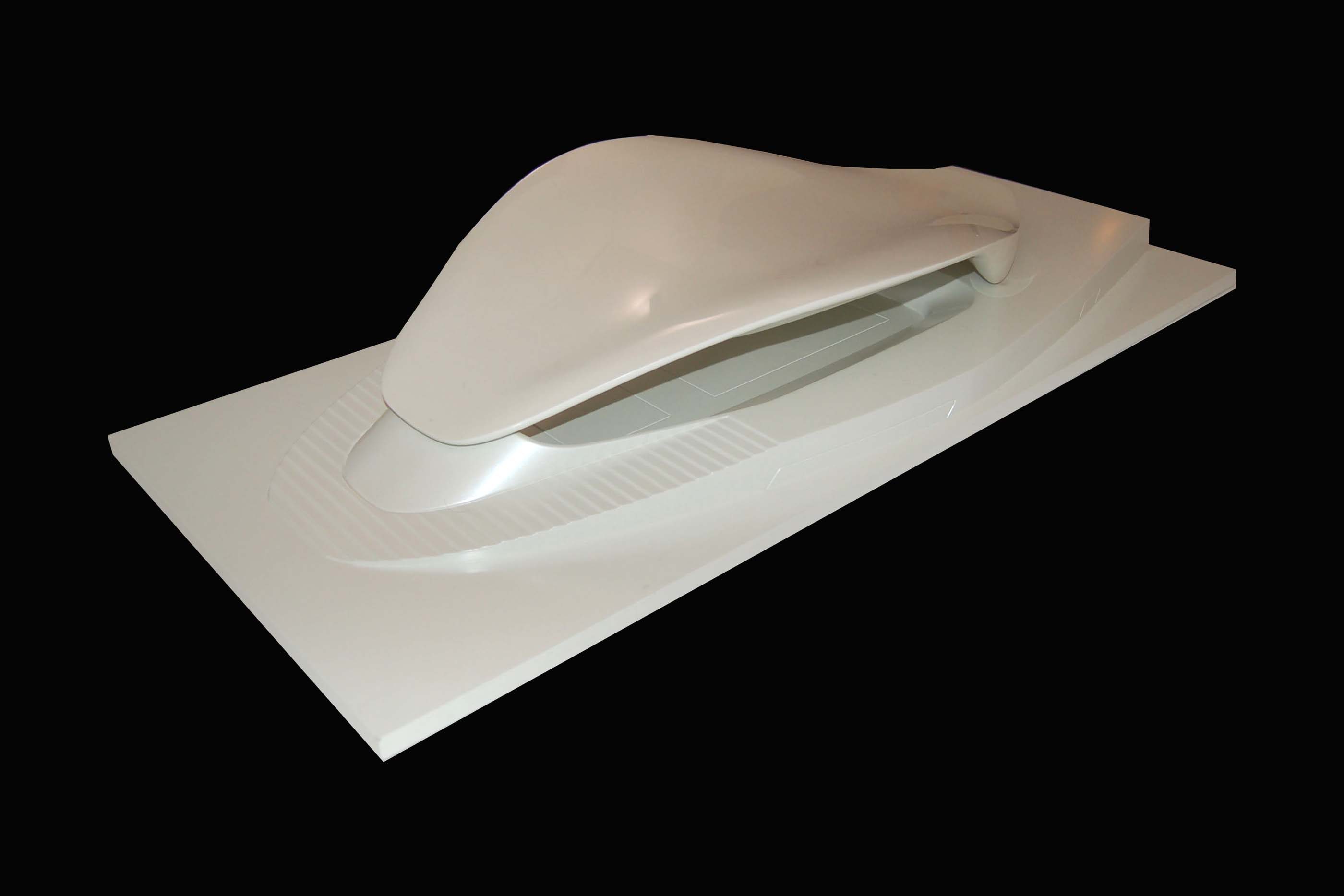

One difference between the two shows was the relative importance of materials. At the Roca Gallery, there is an exploration of sinuous timber, effervescent metals, and glass handbags. Meanwhile, the ZHF’s show focused in on space, activity, and program. One of Hadid’s most materially complex projects—the Olympic Aquatics Centre, once referred to as “seductive béton brut” by architect and critic Peter Buchanan—is included, but the white, plastic, 3D-printed, monolithic form omits the hidden structural wizardry.

The curatorial team faced a significant challenge in mounting this show, as most of Zaha Hadid Architects’ archival collection is yet to be processed. Despite this, they’ve located formative projects like Leicester Square, Blue and Green Scrapers and the prismatic model for Habitable Bridge. The general ambition behind the show—to unearth new perspectives on Hadid’s relationship with London—was a success.

But there’s much more to be seen. Future episodes could study how the realization of Hadid’s swooping shapes changed construction methods or how the ideas incubated during Hadid’s student work in and on London influenced the practice’s approach to working in other contexts worldwide. Reimagining London should therefore be seen as a hint of the archival treasures likely to follow.

Josh Fenton, a trained designer, works in London as a writer and communications consultant.